The Complete Guide to Buying and Owning a Rolex

The Complete Guide to Buying and Owning a Rolex

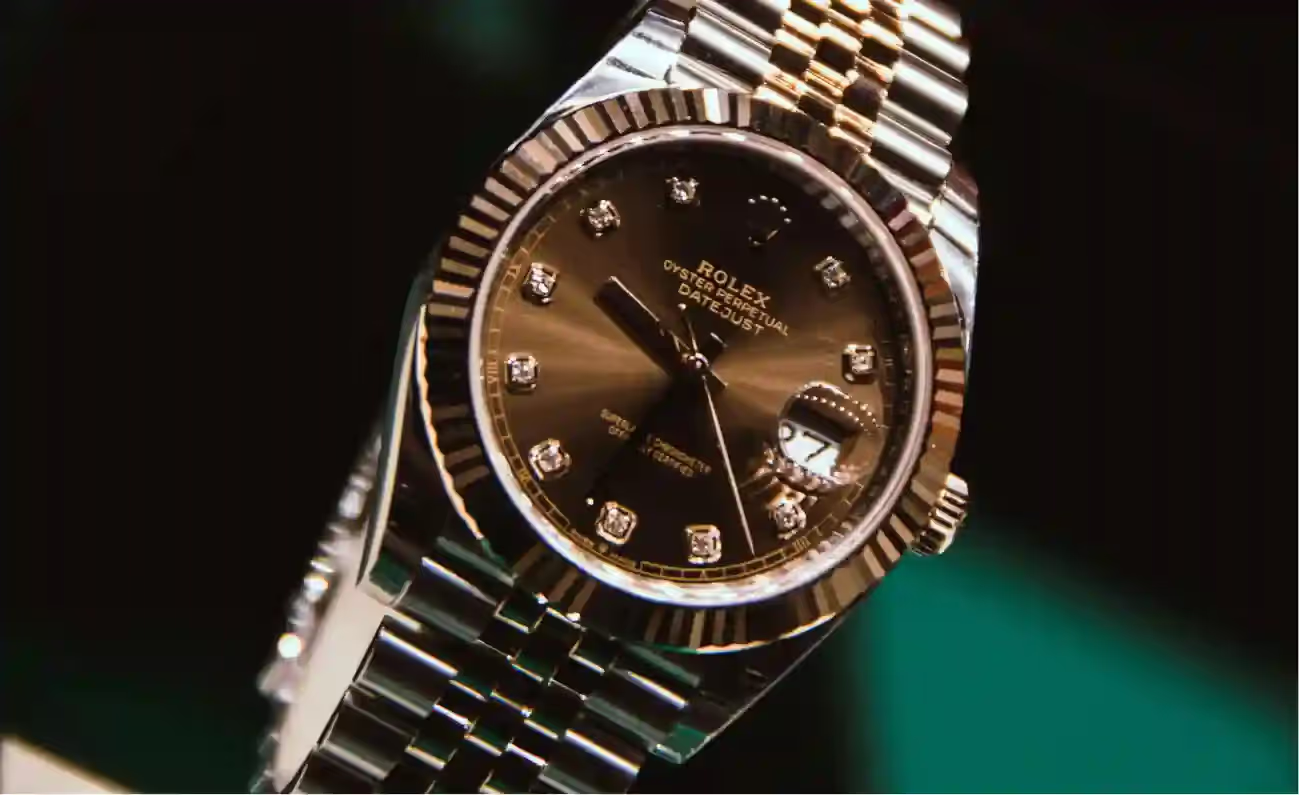

The Significance of Steel and Gold

There exists a moment when you first wear a Rolex that others touch upon in forums or in YouTube reviews but rarely describe. A weight settles gently onto your wrist. It isn't just a heavy bangle of 904L steel or even the eighteen-karat gold, which surely we have a lot of. It's something more than that. You look down at this thing you have maybe saved for, or waited for, or obsessively collected, and suddenly it occurs to you that now you're part of something larger than yourself—perhaps your grandfather wore a Datejust, perhaps your father once coveted a Submariner he saw in a jeweler's window in 1975 but never acquired. Now you have the watch on your wrist, ticking away, completely unconcerned with any of your existential events.

I remember a guy at a watch meet-up in Chicago—he was in his mid-fifties, worked construction his whole life, and his hands looked like tree bark. He was wearing a two-tone Submariner that looked like has been to war. It had scratches everywhere and the bezel insert had faded to a ghost of its former matte black. He told me he went to a jeweler in Milwaukee in 1994 at the end of his first real profitable year of his self-owned contracting business, walked in with cash and bought it. No waitlist, no fanfare, just a handshake and transaction, and he has worn it every day since, including throughout a divorce, through a job site he was working on, to his kid's wedding, and even through chemotherapy. "This watch," he remarked, twisting himself so the afternoon light caught the crystal of the watch, "has better attendance than I do."

The thing about these watches in marketing terms that just can't quite capture, no matter how many times they film young adults in black tie glamourously climbing a yacht gangplank, is that they become witnesses to your life in a way that makes you uncomfortable to think about. Each scratch becomes its own bookmark, in the book of your life. That ding on the bezel, created when you weren't paying attention, smacking your wrist into the door frame as you rushed to your flight. That microscopic scuff on the crystal.... still there, but barely seen, and we both know when it got there. From that night you had too many whiskeys and knocked it into the bar rail. The watch doesn't care; it doesn't judge. It just quietly continues on, accelerating two seconds a day, decelerating two seconds a day, in that range, forever.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Buying New

Let's just call it what it is. Let's forget about talking about the elephant in the room for a dam minute, and rather, let's talk about the vacant demo case in the authorized dealer display. The Rolex buying experience in 2025 is insane. There is a whole parasocial component with how it should work, to how it actually works, that is a level of consistent cognitive dissonance that feels sorry for the American consumer who has a simple, basic understanding of the idea of exchanging goods for money.

You walk into an authorized dealer-and they are often stunning stores, polished marble, low-lit diimmed lights, sales representatives dressed in custom tailored suits-and you ask them about viewing a stainless steel Submariner. Their smile seems automatically in place, patient, but somewhat sorry to tell you their supply. "We don't have any available. Do you want to leave your information?" You're not asking for something out of the ordinary here, you ask to purchase a watch that you know is in production by the company as we speak. But in reality, that Submariner, or that GMT-Master II with the Pepsi bezel, or heaven forbid that steel Daytona, is not for you today. Probably not for you this year.

The allocation system Rolex has is not public knowledge, but if you talk to enough SA's off the record and read enough threads, the picture starts to come together. The watch goes to the person who've made big purchases; it goes to the owners of three precious metal Day-Dates and a platinum Daytona in the last five years. The watch, then, will go to "VIPs." It goes to long-time clients. It goes to the person who the store knows will not sell the watch on the secondary market at a $20,000 profit without giving them the first shot at the watch.

This drives people crazy - and rightfully so. It feels like being denied entry in a club you could otherwise afford. The workarounds people try can be fairly reasonable to a complete absurdity. Some guys play the long-game, starting with a Datejust, maybe the Oyster Perpetual, then building the relationship and proving that they are "serious collectors." Others simply sign lists with different ADs, using their contacts and putting their name on every list in their state, region, and then just keeps hoping. I heard about one guy who bought his wife a "nice" piece of jewelry that she did not want, just to establish a purchase history. A $15,000 diamond bracelet as a deposit on the chance of possibly, maybe, being able to buy a $10,000 watch...

The mental fatigue of this is a very real phenomenon. You find yourself feeling like you're begging someone to let you give them ten thousand dollars. The leverage is completely flipped compared to standard retail, and it breeds resentment. Yet, people still continue to participate in the process, continue to show up every few months to "check in," continue to put their name on a list of some sort, because the other option, being forced to pay double on the grey market is just that much more painful. That's the psychological factor at play.

The Yale of Grey Market

Which brings us to your other option: pre-owned and grey market dealers. These are the Bob's Watches, Crown & Calibers, the DavidSW operations, the Hodinkee Shop. They basically always have what you want, right now, in stock. You can browse their sites just like any other normal shopping experience in the 21st century. I'm going to spend my Saturday morning right now adding a Submariner to my cart, and check out, without even finishing my coffee. When you get these you pay more upfront. The question gets asked, "Is it worth it?" That's what has guys up at night trolling grey market listings at 2AM. Sure you are paying a premium. But you get the watch you really want and that day. You aren't hopeful, you don't have to wait or feel like you are supplicating to a sales associate. For many, especially those with the means, that premium is worth the dignity of the transaction, and for those with means and time to waste, the simplicity of the transaction.

The reputable gray market dealers have also become very good at their business. They provide a warranty, often provided by a Rolex authorized dealer as an independent company. They have trained watchmakers on staff. They authenticate the products rigorously—their living is paid for by their reputation and one fake watch can put a dent in that business they've spent decades building. When purchasing from the reputable gray market, you can be assured you're getting a real watch that has been fully authenticated, often with box and papers, and you are walking away happy, generally, instead of frustrated.

On the flip side, you have the danger zone: the private sellers, the IG dealers, the guy who swears it's real and just doesn't want to meet at a well-lit place. The Rolex counterfeits are goddamn scary. We aren't talking about the $50 Canal Street specials that you can spot from across the room with a trained eye. We are talking about super-fakes that are $1,000 to $3,000 that have cloned movements, the right weight, correct engravings, everything. The only way to know for sure is to open it up and have somebody who knows what to see under a loupe examine it. If you go the private seller route, ask them to meet you at a reputable watchmaker that can authenticate before you exchange cash. If they refuse, walk away. No matter how good the deal seems, no matter how convincing their story, walk away.

The Mechanical Heart

Let's look into what's really happening inside the Oyster case because understanding the movement utterly transforms the watch wearing experience. Modern Rolex calibers (the 3230, the 3285, and the 4130) are not fragile, temperamental little watch mechanisms you have to walk on eggshells around. They are constructed like Swiss bank vaults had love children with diesel engines. Their architecture is designed with one thing in mind; reliability and viability over decades.

Rolex does not give a hoot if watch nerds complain on forums that their movements are not finished like movements from Patek Philippe or A. Lange & Söhne. Generally speaking, the latter movements are nice and pretty and designed to be appreciated from the back of a display case. Rolex movements are designed to be never appreciated until left sealed during the tenure of ownership for ten years at a time. Their movements are designed with simplicity, which is exactly what you want in a tool watch philosophy.

Take for example the Parachrom hairspring. This is not some marketing hype; this is a true watchmaking innovation. Traditional hairsprings are sensitive to magnetic fields (i.e., your iPhone, your laptop computer, that magnetic clasp on your bag), as well are generally sensitive to temperature fluctuation. The Parachrom alloy resolves both. In my experience, I have seen guys wear their Submariners while working under the hoods of car engines, leave them on top of speaker magnets, submit them to every sort of electromagnetic chaos, and the watch keeps running timed within COSC chronometer specs. That wasn't luck; that was engineering.

Chronergy escapement if yet another progression of Rolex that matters more than you might think. By refining the geometry of the escapement mechanism, which is the portion of the movement that converts the energy stored in the mainspring into the alternations of escapement of the regulated tick-tock of the watch, Rolex has improved efficiency by about fifteen percent. This essentially will provide a longer power reserve. The newer movements run about seventy hours as opposed to forty-eight hours. Practically speaking, you can take it off on Friday night and put it back on Monday morning, and it will still be running. You come back from a weekend away, and rather than a dead watch in need of resetting, it is still running.

In a world of Apple Watches and smart devices, there is something tremendously gratifying about wearing a mechanical watch. Every time you check your wrist to see the time, you are accessing time by way of a device powered by your own movements, your being alive and while walking around. There are no batteries or charging cables or software updates. Merely a coiled spring and a balance wheel oscillating back and forth eight times per second and about two hundred other components working together. Yes, it is anachronistic but an anachronism connected to hundreds of years of horological history.

Oh, the Size Question That No One Wants to Truthfully Answer

This is a topic that causes more arguments in forums than religion and politics: what size Rolex should you wear? The internet will tell you it depends upon the size of your wrist and share with you mathematical formulas regarding lug-to-lug measurements and wrist circumference. The reality is more cloudy and personal than any formula would ever cover.

The vintage Rolex aesthetic has been on the rise again: 36 mm cases, thin bezels, and well-proportioned. The closest equivalents would be the 36mm Datejust and perhaps the now discontinued 39mm Explorer (now a 40mm model). These are fantastic sizes. They went under a dress shirt cuff without creating an uncomfortable bump on the wrist. They are understated. A 36mm Datejust has a fascinating ability to look very elegant—and, dare we say, almost European in its simplicity—on the right wrist.

But that said, we do not have to pretend that the current American aesthetic does not skew larger, as the more common/normal dimensions today tend to be 41mm for the Submariner, 40mm for the GMT-Master II, and 42mm for the Explorer II. These larger models have presence—they wear well on the wrist. They generally are easier to read at a glance. And, yes, they are more prominent on the wrist, which is part of the intention for some people.

I've seen guys wearing 36mm Datejusts with a seven-inch wrist and they look great. And, I've also seen guys wearing 42mm Sea-Dwellers with the same wrist size and it looks great. I've even seen NBA players wearing 36mm vintage pieces that look ridiculous on their wrist, and the same guys wearing 44mm Panerai watches that look totally normal. Overall, there are no rules to size. Just find a watch that you feel good wearing. If the 41mm Submariner for example feels like you have a dinner plate on your wrist, go smaller. If the 36mm Datejust on the other hand feels invisible, go larger. And, listen to your gut over the internet mathematical formulas for sizing.

One thing worth considering: Suppose you're purchasing your first Rolex for the purpose of wearing it every day for the next 20 or so years. If you are in doubt between a 36mm watch and a 44mm watch, steer towards the mid-size. 40-41mm will be suitable for every "normal" situation you wear a watch for, and it won't go out of style over multiple decades if fashions turn. But honestly—if you love it, wear it. You're only here for limited time, so why not wear a watch that brings you bliss instead of worry about when the opinion of perfect strangers on the internet about mm fits your wrist?

The Bracelet That Ruined ALL Other Bracelets

Let's take a moment to appreciate, in what could be viewed as the most underrated thing about a Rolex, the bracelet. After you wear an Oyster or Jubilee bracelet for a few months on your wrist, you put on another type of watch bracelet, and it feels like you just left your Mercedes for a Kia. That is actually how drastic the difference feels.

The Oyster is the workhorse. Seamless, reliable, three-piece link, solid built, you can torture them. For this current generation of Oyster bracelets, the links are attached using screws instead of pins, so they do not loosen over time like an older vintage style. The visual flow from the lugs down to the bracelet is tapered in such a manner that it makes the watch appear like it is supposed to be integrated, not just some case with an afterthought wrist strap. And the clasp, the Oysterlock with the Easylink extension, are an engineering miracle. You can enlarge the bracelet by 5mm at your wrist, without any tools. Say you did a workout and the wrist swelled? Easylink. When you moved to summer, and your wrist swells? Easylink. Flying with cabin pressure changes? Easylink. It is precisely the type of feature you never knew you needed until you have it, and then you cannot imagine living without it.

The Jubilee bracelet is a flasher, five-piece links that catch light with every movement. The Jubilee is the bracelet on the Datejust, on its vintage GMT-Masters, and on the current Pepsi GMT. It is more flexible than the Oyster, so it can feel less rigid, which makes it comfortable for some folks. It is also less sporty, so it has more of a classy look. The scuttlebutt is that it is not as solid. At least, the Jubilee bracelet's robustness can seem less, but that is just in comparison—not because the Jubilee is fragile. If you will actually be wearing your watch and doing physical labor with it, chaos, the Oyster would probably be a better option.

Then there is the President bracelet worn only on the Day-Date and certain models of Datejust in precious metals. Semi-circular three-piece links that flow like liquid gold (or platinum) on the wrist. It's the most comfortable bracelet Rolex makes, bar none. It's also the loudest, in terms of visual presence. You cannot wear a Day-Date on a President bracelet and have it be subtle. That's not what it's for. It's a declaration.

The Vintage Rabbit Hole

At some point in every Rolex enthusiast's journey, they start looking at vintage pieces. This is both exciting and dangerous, because vintage Rolex collecting is a deep, complex rabbit hole that has swallowed many good men whole, along with their bank accounts.

The appeal is obvious. Vintage Rolex watches have a soul that modern pieces, for all their superior technology, sometimes lack. The patina on a tropical dial—where UV exposure has turned the original black or brown to a gorgeous faded chocolate. The luminous material that's aged from white to cream to butterscotch. The Ghost bezel on a vintage Submariner, where the original black has faded to a silvery gray. These aren't flaws. They're character. They're proof that the watch has lived.

Prices in the vintage market are all over the map, which makes it both opportunity and minefield. A 1960s Datejust in steel with a simple dial can be had for $4,000 to $6,000 if you're patient. A Paul Newman Daytona in the right configuration? Try seven figures. Most vintage collecting happens in between these extremes. A nice 1970s Submariner might run $15,000 to $25,000 depending on condition and reference. A vintage GMT-Master from the 1980s could be $12,000 to $20,000.

But here's where it gets tricky: authenticity and originality. The vintage Rolex market is absolutely rife with Franken-watches—pieces that are genuine Rolex, but assembled from parts that were never meant to be together. A 1680 Submariner case with a 1665 dial and a 5513 bezel insert and a 1016 movement. All real Rolex parts, technically, but not a real Rolex watch. These Frankens can be difficult to spot if you don't know what you're looking for, and they're worth a fraction of what an all-original example would be.

Then there are the outright fakes, and at the vintage level, these can be sophisticated. Service dials (replacement dials installed during factory service) versus original dials is a whole contentious debate. Relumed hands and dials. Replaced bezels. Every component's originality affects value, sometimes dramatically. A vintage Daytona with an original dial might be worth $50,000; the same watch with a replacement dial might be $25,000.

If you're going to venture into vintage collecting, you need to either become an expert yourself—which takes years of study, handling hundreds of watches, making expensive mistakes—or you need to buy only from dealers with impeccable reputations who specialize in vintage Rolex. Phillips Watches, Sotheby's, Analog Shift, Wind Vintage—these are the kinds of operations where you pay premium prices, but you're paying for expertise and authentication that you can trust.

The Rolex You Never Knew You Wanted

One of the interesting psychological phenomena in Rolex collecting is how many people end up loving watches they initially dismissed. Guy wants a Submariner, can't get one, tries on a DateJust 36mm in white gold on a Jubilee bracelet just for the hell of it, and suddenly realizes that this elegant, understated piece might actually be more his style than the dive watch he'd fixated on.

The Oyster Perpetual line, especially in the newer 36mm size with the bright dial colors, has become quietly popular. These are pure time-only watches—no date, no complications, just hours, minutes, and seconds. They're the entry point to the Oyster case architecture at around $6,000 to $7,000 retail (if you can find one). The coral red dial, the turquoise blue, the candy pink—these are not your grandfather's Rolex colors. They're playful and modern, and on the right person, they work brilliantly.

The Air-King is another watch that people sleep on. It's odd-looking, admittedly. The combination of the 3-6-9 numerals with the big triangle at 12 o'clock creates a dial that's busy and tool-ish in a way that divides opinion. But in person, on the wrist, it has tremendous charm. It's also one of the few current-production Rolex sports watches you might actually find at an AD, because the demand isn't insane.

And can we talk about the Milgauss? This thing was designed for scientists working around electromagnetic fields—CERN researchers, engineers, people whose daily environment would scramble a normal watch. It has that funky lightning-bolt seconds hand and the green sapphire crystal that gives the dial a subtle tint. Nobody's buying a Milgauss because they need its anti-magnetic properties. They're buying it because it's weird and cool and different from every other Rolex out there.

The bottom line is, if you are in allocation hell for the watch everyone is after, then take some time to try and wear the watches that don't inspire the same craze. You may be surprised.

End Thoughts on Steel and Legacy

Here is what no one tells you about finally getting the Rolex you have been dying to get, the joy wears off nearly as fast as you would expect, but the satisfaction lasts forever and out-lives each of us. In the first week, you will look at your wrist every 3 minutes, you will find every excuse to talk about watches with anyone willing to listen, and you will spend hours on the internet reading about your specific reference, the production years, and the variations in movement you've learned about that don't really matter but feel significant nonetheless.

After that, you begin to return to normal life. Your watch is that nice thing you wear on your wrist. You eventually fee like you don' think about it consciously anymore. It is simply there wking as it should be. That is where the relationship with the watch actually begins. That is where it stops being just an acquisition and starts to be the tool that it truly is.

One day, you look down at your wrist and realize you have had the watch for 6 months already; it has quietly ticked away for all of this time keeping track of time for you. It hasn't asked anything of you this whole time. It could be worth everything regarding the money you spent, the month-long wait, and the obsessively anxious moments of wondering if it was all worth it. Whether-or-not "worth it" is a question regarding value is a personal and subjective experience.

If all you really want is a reliable watch that tells the time accurately -- just buy a Seiko or a Grand Seiko and save yourself $10,000 and the emotional roller coaster. If you want an object of significance, a piece of art that connects you to 100 years of human achievement, and that will last longer than you and be someone else's story for continued generations- then yes - it is worth whatever you had to spend on it and all the time you had to wait for it.

The watch on your wrist is keeping time for you today but it will also keep the time at some later point for a new owner. None of that would ever happen without your original investment. That is the deal. That is the meaning in this practice. That is why any of this matters.